1M HTTP Requests per second using Nginx and Ubuntu 12.04 on EC2

Table of contents

At work, we have been doing quite a few tests lately to understand what is the maximum number of http queries per second (QPS) that a modern server running Ubuntu 12.04 with a recent Linux kernel could handle.

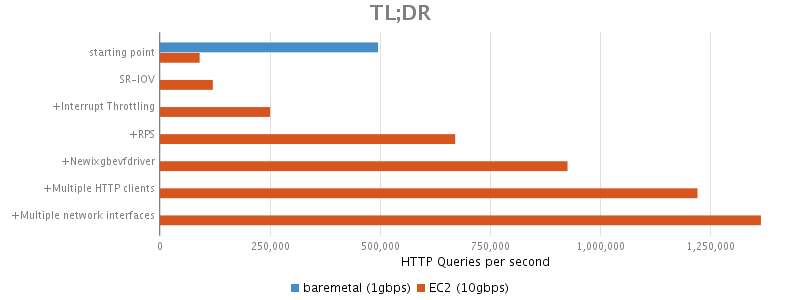

In our initial testing on our local bare metal development servers, we were able to reach ~495k QPS. At first sight, this might look like a large number of queries, but we were in fact limited by the bandwidth available on the network. These machines have a 1Gbps network interface and it was saturated by our test... so they were unsuitable for our benchmarks.

We set out to reproduce the benchmark on machines which have 10gbps NICs to see how high it would go. We booted big amazon servers (c3.8xlarge) and encountered quite a few issues trying to even match our baremetal numbers...

The following explains what was done in order to reach ~925k QPS between 2 c3.8xlarge instances on amazon ec2 and how we eventually reached 1364k QPS when using more than one http client and 2 elastic network interfaces.

Test setup

The benchmark is very synthetic in nature, the clients are doing as many GET / as they can and the server replies with a very small HTTP 200 response.

The tests were done with c3.8xlarge (HVM) instances on amazon ec2 using the stock ubuntu 12.04 image, but the kernel was upgraded to the latest available at the time: 3.13.0-61. This distribution is not exactly cutting edge, but that's what we currently deploy in production, so we wanted to stick with it to do the tests in order to be discover its limits and to be able to apply configuration tweaks that we might discover.

On the client machines, we used httpress to send out requests to nginx over 1000 keepalive connections using 16 threads:

httpress -n 30000000 -t 16 -c 1000 -k http://10.1.1.1/

[...]

TOTALS: 1000 connect, 20000000 requests, 19999943 success, 57 fail, 1000 (1000) real concurrency

TRAFFIC: 0 avg bytes, 160 avg overhead, 0 bytes, 3199990880 overhead

TIMING: 21.629 seconds, 924679 rps, 144481 kbps, 1.1 ms avg req time

On the server machine, nginx was configured to return a small but complete 'HTTP 200' reply from 16 workers.

worker_processes 16;

events {

worker_connections 4096;

accept_mutex off;

# multi_accept on;

}

http {

...

keepalive_requests 100000000000;

...

}

server {

listen 80;

access_log off;

root html;

index index.html index.htm;

location / {

return 200;

}

}

Initial results

To our dismay, when running the same benchmark on the Big Amazon Machines™, we could not even go over 100k QPS, in fact we barely got over ~925k QPS. That was unexpected...

To understand what was going on, we ran the benchmark a few times and launched perf top -g -F 99 while it was running.

This showed that ~30% of the machine time was spent in some spinlock in the network stack.

Uh, not good.

- 36.21% [kernel] [k] _raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore

- _raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore

- 80.09% __wake_up_sync_key

sock_def_readable

tcp_rcv_established

tcp_v4_do_rcv

tcp_v4_rcv

ip_local_deliver_finish

ip_local_deliver

ip_rcv_finish

ip_rcv

__netif_receive_skb

netif_receive_skb

handle_incoming_queue

xennet_poll

net_rx_action

__do_softirq

call_softirq

do_softirq

SR-IOV - Take 1

On EC2, there's a feature called Enhanced Networking that is supposed to significantly increase the network performance. The feature is only available on a few instance types: c3, c4, d2, m4 and r3.

On these instances, when SR-IOV is enabled,

the kernel will use the ixgbevf network driver instead of the generic wif driver, which allows it to talk directly to the hardware.

By default, the official Ubuntu 12.04 image available on EC2 do not have SR-IOV enabled. It is possible to see it by running the following command on a vanilla 12.04 instance:

aws ec2 describe-instance-attribute --instance-id instance_id --attribute sriovNetSupport

# no output

Enabling the feature on ubuntu 12.04 requires a few steps:

- The kernel must be upgraded. In our tests we used 3.13.0-61 which was the latest at the time.

- Stop the 12.04 instance

- Enable Enhanced Networking from the awscli client:

aws ec2 modify-instance-attribute --instance-id instance_id --sriov-net-support simple

- Boot the instance

- Verify that the network interface uses the ixgbevf network driver:

ethtool -i eth0

# This should show ixgbevf as the driver

With SR-IOV enabled, we reached ~120k QPS, it is better, but still much lower than expected...

Interrupt Throttling

When doing the benchmark above, htop showed us that 1 CPU was running at 100% in system time.

It turns out that the ixgbevf driver has a single receive queue, and thus receive interrupts are handled by a single CPU.

This can be observed by grepping for 'eth0-TxRx' in /proc/interrupts:

260: 3873 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 xen-pirq-msi-x eth0-TxRx-0

To reduce the amount of CPU time required to process incoming packets, the driver has a feature called InterruptThrottleRate which, as its name implies, can reduce the rate at which interrupts are fired at the cost of slightly increased latency.

Enabling this feature requires a reload of the network driver (or a reboot):

echo "options ixgbevf InterruptThrottleRate=1" > /etc/modprobe.d/ixgbevf.conf # 1 means 'dynamic mode'

reboot

With this feature enabled, we could reach ~250k QPS. A nice improvement, but still 50% slower than our baseline on bare metal...

Receive Packet Steering

One way of achieving high performance in inbound packet processing is by using multiple 'receive queues' in the network drivers when the underlying hardware supports it.

This allows each queue to be assigned to a CPU and thus spread the interrupts to more than a single CPU.

However, the ixgbevf driver does not support this scheme in the version available on ubuntu 12.04 (2.11.3-k - more on this later).

Folks at google devised a clever scheme called Receive Packet Steering that allows the kernel to emulate this multiqueue behaviour at a layer up in the stack:

[...] RPS selects the CPU to perform protocol processing

above the interrupt handler. This is accomplished by placing the packet

on the desired CPU’s backlog queue and waking up the CPU for processing.

RPS has some advantages over RSS: 1) it can be used with any NIC,

2) software filters can easily be added to hash over new protocols,

3) it does not increase hardware device interrupt rate (although it does

introduce inter-processor interrupts (IPIs)).

RPS is called during bottom half of the receive interrupt handler, when

a driver sends a packet up the network stack with netif_rx() or

netif_receive_skb(). These call the get_rps_cpu() function, which

selects the queue that should process a packet.

To enable this feature, we need to fiddle with /sys/class/net/<dev>/queues/rx-<n>/rps_cpus, a file which contains a bitmap of CPUs allowed to process packets from this receive queue.

More documentation on the format of this file can be found here:

- https://www.suse.com/support/kb/doc.php?id=7015585

- https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-US/Red_Hat_Enterprise_Linux/6/html/Performance_Tuning_Guide/network-rps.html

The easiest way to enable RPS is to enable all CPUs to process the packets, however, this does NOT give the best performance:

echo 'ffffffff' > /sys/class/net/eth0/queues/rx-0/rps_cpus # That's _not_ much better than having it turned off

In our test, this gave very little performance gain, we were still at ~250k QPS.

We experimented with the bitmask and tried multiple combinations to find the optimal settings. In our case, the interrupts for the receive queue were set to fire on CPU 16:

| CPUs enabled for RPS | QPS | bitmask |

|---|---|---|

| No CPUs | 250k | 0000 0000 |

| All CPUs (32) | 250k | ffff ffff |

| All CPUs except the one handling interrupts (31) | 515k | fffe ffff |

| All CPUs in the same NUMA domain as the one handling the interrupts (16) | 300k | ffff 0000 |

| All CPUs in same NUMA domain as the interrupts except the one handling interrupts (15) | 590k | fffe 0000 |

| 7 CPUs in the same NUMA domain as the interrupts | 670k | 00fe 0000 |

A side note: we tried using the CPUs in the other NUMA domain and expected to have really bad results. It turns out that the numbers are slightly lower, but it is not nearly as bad as we expected.

We used lstopo to understand what the NUMA topology of our machine was. This command is available from the hwloc ubuntu package.

To control all the variables in this test, it is best to manually tell the kernel where the interrupts should go instead of doing guess work.

# First get the interrupt number (260 in our case)

grep eth0-TxRx /proc/interrupts | awk -F: '{print $1}'

260

# Then set CPU affinity of the interrupts to CPU0:

echo 00000001 > /proc/irq/260/smp_affinity

# Configure RPS on 7 CPUs in the same NUMA domain as CPU0

echo '000000fe' >/sys/class/net/eth0/queues/rx-0/rps_cpus

SR-IOV Take 2

670k QPS is great, but we though it could do a bit better.

With the RPS settings listed above, there are 7 + 1 CPUs dedicated to handling network packets, that leaves 24 cores to the applications and they're pretty much idle in our benchmark. Maybe the newest version of the ixgbevf driver had some performance tweak?

Compiling this driver is relatively straight forward, but because of some symbol mismatch between the ubuntu kernel and what the driver expects, it is not possible to compile versions newer than 2.11.3 on ubuntu 12.04. This is probably easily solvable by patching the driver's source, but we have not investigated this yet.

To compile and enable the newest (compatible) version of the driver (as per https://gist.github.com/CBarraford/8850424):

apt-get install build-essential

apt-get install linux-headers-YOUR_KERNEL_VERSION-generic

wget "http://downloads.sourceforge.net/project/e1000/ixgbevf stable/2.11.3/ixgbevf-2.11.3.tar.gz"

tar -zxf ./ixgbevf-*

cd ixgbevf*/src

make install

modprobe ixgbevf

sudo update-initramfs -c -k all

reboot

This new revision of the driver has 2 RxTx queues, so it allows for 2 CPUs servicing interrupts. (Based on this bug report, 2 queues is the hardware limit.)

Using the same technique as above, we achieved the best results by having interrupts handled in separate NUMA domains and by doing RPS on 7 CPUs, each in the same NUMA domain as the CPUs handling the interrupts in that domain.

For example, in our tests we set interrupts to fire on CPU0 for queue rx0 and on CPU16 for queue rx1, and we set the masks as follows:

# Find interrupt number

grep eth0-TxRx /proc/interrupts | awk -F: '{print $1}'

260

261

# Set CPU affinity of the interrupts to CPU0 and CPU16:

echo 00000001 > /proc/irq/260/smp_affinity

echo 00010000 > /proc/irq/261/smp_affinity

# Set RPS for 7 CPUs in the same NUMA domain as the interrupt CPU

echo '000000fe' >/sys/class/net/eth0/queues/rx-0/rps_cpus

echo '00fe0000' >/sys/class/net/eth0/queues/rx-1/rps_cpus

Using this configuration we were able to achieve 926k QPS.

Breaking the 1M QPS barrier

Multiple Clients

During the last test above, we saw that the client machine was 100% busy on most of its cores, while the server had ~12 cores mostly free. So we thought it would be possible to push the server performance even further by using more than one client.

Indeed, using 2 clients with the same configuration as above, both of them were able to do ~610k QPS, for a total of ~1220kQPS. Hey we're getting somewhere!

Multiple network interfaces on server

Based on our earlier observations, we knew that the machines were CPU bound and that the hottest spot was the interrupt handling for network interface. In previous tests, we had 2 receive queues / 2 interrupt sources for received packets for our network interface. Thus, we had 2 CPUs saturated with handling those interrupts.

If we had a way to add more receive queues, and thus more interrupt sources, we could keep other CPU cores busy with those interrupts.

It turns out that it is possible to attach new network interfaces to an EC2 instance via a feature called Elastic Network Interfaces (ENI), so we wanted to test the performance of the server machine with the following parameters:

- 2 network interfaces

- Each interface's receive queue interrupts configured to go to a specific CPU

- Have 7 CPU handle the packets from those interrupts via RPS

To be able to test this, we needed 2 clients, each of them would hammer one of the server's network interface.

Since the new network interface was in the same subnet as first one and the clients are in the same subnet as the server, we needed to add a static route to reach the ip of our second client via our new interface:

route add CLIENT_IP dev eth1

The following interrupt affinity and RPS configuration was used:

# we set CPU affinity of the interrupts

echo 00000001 > /proc/irq/260/smp_affinity

echo 00010000 > /proc/irq/261/smp_affinity

echo 00000100 > /proc/irq/263/smp_affinity

echo 01000000 > /proc/irq/264/smp_affinity

# set RPS

echo '000000fe' > /sys/class/net/eth0/queues/rx-0/rps_cpus

echo '00fe0000' > /sys/class/net/eth0/queues/rx-1/rps_cpus

echo '0000fe00' > /sys/class/net/eth1/queues/rx-0/rps_cpus

echo 'fe000000' > /sys/class/net/eth1/queues/rx-1/rps_cpus

With this configuration we reached ~1364k QPS and all CPU cores were pretty much busy...

Other things we tried

Clock source

By default, in the ubuntu image we use on amazon, the clock source is 'xen', which is somewhat slower than what we find or baremetal machines.

Since the routines to fetch the time of the day kept showing up pretty high in the perf profiles we took during those benchmarks, we tried changing to the tsc clocksource.

It does have an impact on performance, but in the benchmark it didn't give an amazing boost. Nonetheless I would recommend to use it:

echo tsc > /sys/devices/system/clocksource/clocksource0/current_clocksource

CPU Pinning

We tried to pin nginx workers to sets of CPUs, but no matter how we arranged the CPU mask, we could not get better performance than what we had above.

We have not done extensive testing regarding this technique, but at first sight it doesn't seem very promising.

Maybe pinning would be more beneficial on the client side?

Conclusions

In light of all the tests we did, the best performance for this particular benchmark was achieved using the following configuration:

- c3.8xlarge HVM running ubuntu 12.04

- Latest 3.13 kernel available (3.13.0-61)

- SR-IOV enabled on the instance

- Latest compatible version of the ixgbevf network driver. (2.11.3)

- this version has 2 receive queues, allows to spread interrupts load on 2 CPUs

- InterruptThrottleRate in dynamic mode.

- Reduces the interrupt rate, lets the CPU handle more packets per interrupt

- Receive Packet Steering to spread packet handling load to multiple CPU

- Set CPU mask to keep packets in the same NUMA domain as the CPU handling the interrupts.

- Performance does not scale linearly when adding CPUs to RPS.

- Using 7 CPUs gave the best performance for our benchmark (realworld use will probably differ).

- The CPU handling the interrupts should NOT be enabled in the CPU bitmask. doing so kills the performance

Applications in our products

We do not currently have a need to handle above 250k QPS on a single server, so it is unlikely that we'll deploy all of these tweaks to our production environment.

Nonetheless, it is quite useful to understand the current limits of the environment and how we could scale it from its current limit of ~70k QPS up to 1M+ QPS.

We will probably be deploying part of these measures which require minimal effort and maintenance but still allow to lift the QPS limit up to 250k QPS:

- enable SR-IOV on our instances supporting it (keeping the original 2.11.3-k driver with a single rx queue)

- enable interrupt throttling

That's simple enough and gives an appreciable performance gain.

Further exploration

I'd be really curious to run this benchmark again on the C4.8xlarge instance type. These monsters have 36 cores so we can probably squeeze a bit more performance out of them.

It would also be interresting to test the latest version of the ixgbevf driver (2.16.x) to see how it compares to the ancient version available for ubuntu 12.04.

Yes yes... I know, we should upgrade to 14.04, but at this point waiting for 16.04 might be a better time investment.

Besides, the most recent version don't compile on 14.04 either, it seems like it still needs a patch.